“This t shirt saved my life,” Hannatu Yusuf confirms, clutching a tattered white shirt. “When I ran to escape Boko Haram, my chest was bare. All my children and I were barefoot, too. They had no clothes on either and it was very cold at that time. We were in the forest, sleeping on the ground. I found this shirt and put it on. It kept me safer.”

The family had to flee so suddenly, they didn’t even have time to get dressed as they sprang from slumber on that hot evening. While her family was lacking clothes, others had the opposite problem, removing shirts and pants so they could run to safety more quickly, she explains, so she was able to find something to wear.

Though covering her bare chest made her feel safer against Boko Haram, the armed group still captured her and her children.

“That one week we spent with [Boko Haram], there was no form of suffering we didn’t face. They were not giving us food,” Hannatu laments. “There was no place to sleep. We had to sweep dirt away with our hands to sleep on the ground. During the daytime, they would tell us to sit down. They surrounded us with their guns.”

Hannatu was freed, but Boko Haram held her daughter captive for one month. “She was 10-years-old when they abducted her. They even beat her when they [took] her. They kept beating her.” Fortunately, a woman helped her sneak away and reunite with her mother. “She was covered in bruises and cuts when she returned,” Hannatu says, clearly disturbed by the bittersweet memory.

The 37-year-old mother, her daughter, and her eight other children were given a drive to Maiduguri a few days later from government officials. Despite the city being the birthplace of Boko Haram and the capital of Borno, the state at the centre of the conflict in Nigeria, now in its ninth year, Maiduguri offers relative safety, camps with rows of tarpaulin tents for displaced families, and humanitarian aid from national and international organizations.

“I didn’t enjoy either of the two camps we stayed at,” Hannatu says, adding that the second – where she has lived with her children for the last two years – offers no farmland and sees some 200 displaced people living on a property about the size of a football field.

“If I think of the life we had, I just cry. My youngest son, Gabriel, is four-years-old. My oldest is 20. That’s Roseline. If my children think of everything Boko Haram destroyed, they would lose their minds. A church has sponsored the youngest ones to go to school, but today they left having eaten only a few bites of fried dough. When they come home, there will be no food to give them. Sometimes we spend one week just eating flour and sugar.”

“Back home in Baga, we were farming, my husband and me. Beans. Maize. Onion. Groundnut. Okra. We farmed it all. There was no hunger. We had fish everywhere,” she recalls fondly.

“We ate and drank. We also had a shop where we sold groceries. I paid people to work there so I could tend to the farm. And if someone comes to visit, we’d even give them [something] to cook. Since coming here as migrants three years ago, we don’t have the ability to go and find food. If we’re not given any, we live in hunger.”

“I am from Cameroon though I lived with my Nigerian husband in Baga for 12 years. I don’t know anyone in Maiduguri. My relatives are not here helping me. I cannot say my husband’s relatives are helping me either. I can only hope for the kindness of strangers; that God might compel someone to help us – to look at us and say, ‘take this and cook it for your children.’”

“Some of my children are healthy. Some are not. You saw my son. He has been sick for three days. If I had money, you wouldn’t see him sitting here – I would take him to the hospital. As soon as he is better, another child will fall sick. I am also not well. If you look at me, you know I’m hardly eating: I sit hunched because there’s no food inside my stomach.”

“Our life was very different before; my husband would bring me boxes of fish. We cooked our food without suffering any problems. My husband was alive and healthy. It was here that he died. We never saw him sick before. Once he lay down, he never woke up. It’s been one year now. I have children. And there is no food.”

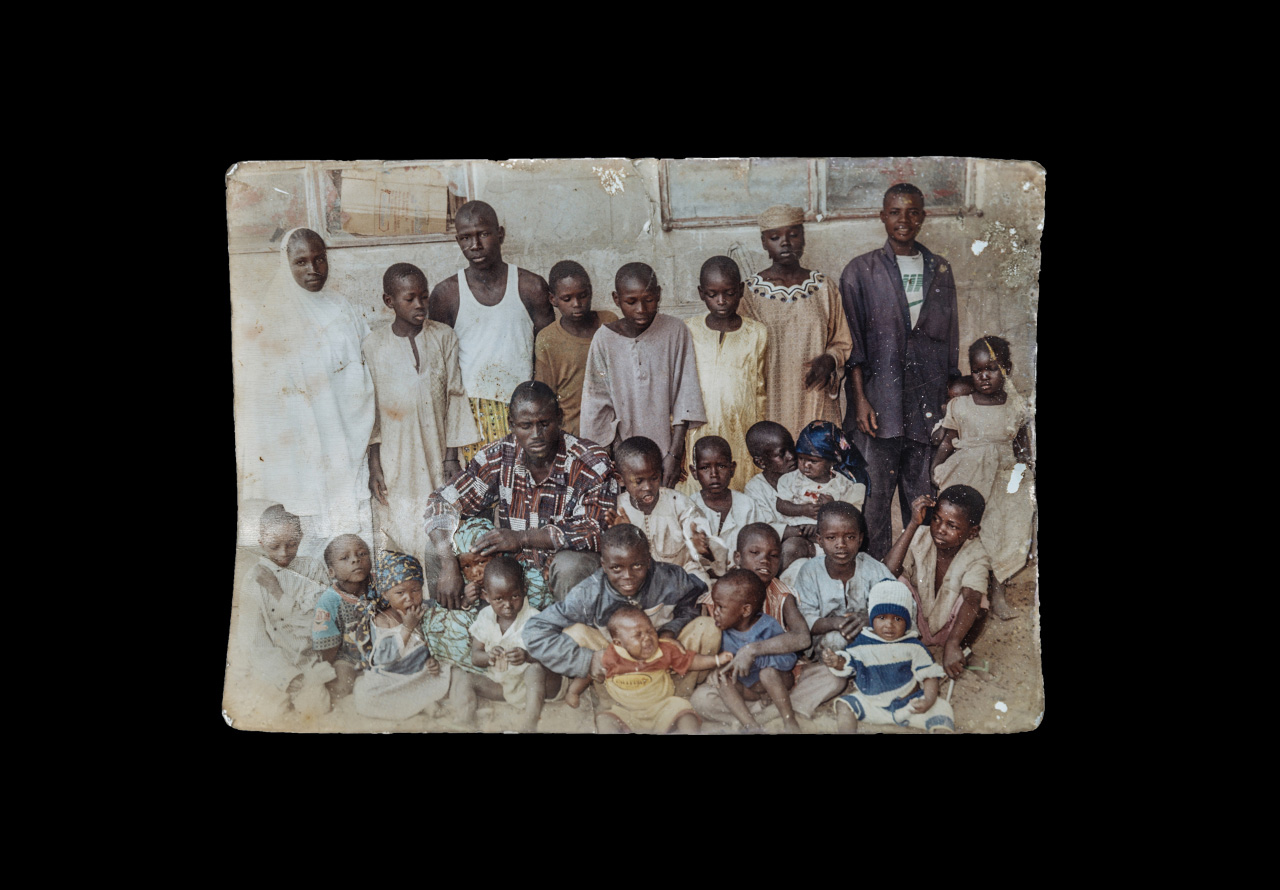

Hannatu, her nine children and two grandchildren all sleep on the ground in a structure they built out of tin walls with sticks, shreds of tarpaulin and rags for roofing. They live among other displaced families in a sandy yard a local church donated in Maiduguri. She says they all get along well – “we are all suffering so much. Why would we fight? We don’t know what to do. If we remember all the happiness we felt in Baga then we will gather under a shaded area together. If we think and think, all of us will start crying.”

“Even if there is no food around, [my husband] would go and buy some with the money he got as a labourer. If you enter the room where we sleep, you see holes in the roof. In the rainy season, none of us here sleeps at night. We sit awake all night as the rain pours, waiting for it to slow so we can empty the water from where it has gathered. If [my husband] was alive, he would know what to do. He would know how to stop the leak. Every day, I’m in tears and always sick.”

“My husband would ask us, ‘what will we do?’ I’d say, ‘I’d prefer to die than suffer like this; no food and there are children.’ He’d reply, ‘if you die, I’ll suffer even more, but what can we do? There are no jobs.’ After all, he left me and I’m following his footsteps. The world continues to be so difficult. It’s not stable, what will you think? My thinking is... is it tomorrow or later that death will come for me? I’m just waiting for my death.”

Hannatu is holding on, just barely. She smiles as she pets and plays with their dog, Gamshi, in the small area she has fenced around their makeshift home. One of her eldest sons keeps chickens there even though she knows they couldn’t afford them. She wanted him to have something to care for, she says.

Like so many mothers, she tries her best to help her children with their homework, joining her son, still in his checkered school uniform from the day, to read through his math exercises. Sun shines in from through the cracks in the fence she has handwoven out of straw, dotting their faces with freckles of light. Hannatu finds such moments of tranquility in the life that has become so stressful for the young mother who has lost her husband, her home, and her livelihood. They do not know when it will be safe enough to return to their beloved town, Baga.

Hannatu is also holding on to the one thing she still has from Baga: that large, torn, cotton t-shirt, which bears the logo of a local pesticide company written in white with red and evergreen details.

“Now, the shirt is worn down. I should put it in the fire like I do with other old clothes, but I won’t because it’s the one that kept me safe,” she explains. “It seems like my husband to me. I will keep this for my children as part of our history of when we fled like that, [naked]. I will sew it into the inside of my pillow so that I always have it with me. I will not leave it out for the children to play with,” she says as she folds it tenderly to put it away in an old canvas sack.

“Whenever I think of it, I go and find it. I put it on because it’s this very shirt that saved me from danger. I’ll never forget this shirt,” she says with her biggest smile yet.