“One by one, the achievements of a lifetime, all of it was gone. My Nikon D60 is gone. My Yashica, an original Japanese camera, and many other things I cherished are gone. This camera and an old video camera were supposed to be the last things to go but I couldn’t bring myself to sell them.”

Life was pretty good for the wedding photographer of south Mosul until mid-summer 2014, when a six-day ISIS offensive against the Iraqi Army resulted in the capture of the historic city on the banks of the Tigris river 400km north of Baghdad.

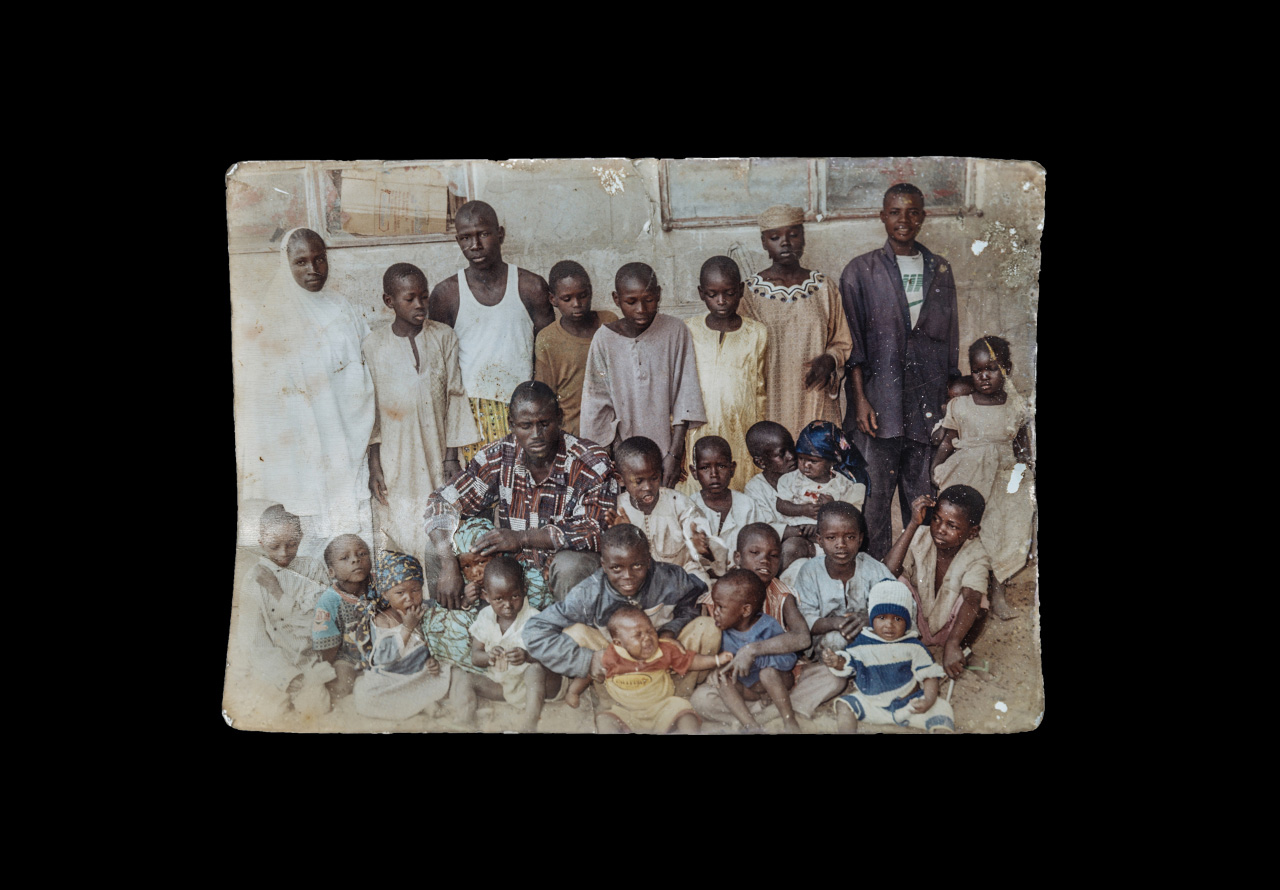

“Before this new generation of digital cameras hit the market, back in the day, I bought this point-and-shoot camera and memory card for 300 US dollars,” says Moafaq, holding a battered Sony Cybershot, his lone remaining stills camera from what was once an impressive collection. “I used this camera for the first wedding party and it paid off. People really liked the results.” His small business filming and shooting weddings and other happy moments dried up in the face of ISIS’ brutal occupation when photography of any kind was forbidden. Life became increasingly difficult and escape, nearly impossible for those like Moafaq who chose to remain with his wife and four children in their home neighbourhood of Tal Abta.

When the Iraqi army announced plans for a massive operation to reclaim the city that was once home to 1.8 million people, Moafaq and tens of thousands of others trapped in Mosul began a frantic race to stock up on the food and water they would need to survive the siege. In a moment of desperation, he started selling everything he had including his beloved cameras.

As the battle raged, Moafaq finally decided to take a chance and flee. “We left our home on 26 November, 2017, a date I will never forget.” His wife put the remaining cameras in the car first, tucked under the driver’s seat so they would not be forgotten. “She said, ‘keep it, maybe one day things will be back to normal and you can start anew with it until you can afford better’.” The family walked three kilometers to a valley the locals call called Al Wadi in an effort to avoid the clashes and crossfire where they survived for the next month, before reaching a camp for internally displaced people in Qayara, 60kms from Mosul, in January 2018.

When they first arrived at the camp they were broke. At one point, the circumstances were so dire that Moafaq contemplated on selling his final cameras to make ends meet. His wife immediately rejected the notion, selling her gold earrings instead.

“This camera carries a lot of memories. I used it to take pictures of my children at home. We used to go north to picnic and these cameras were always with us. We took pictures and video footage that I still keep as memories,” he says. Moafaq and his family remain in the IDP camp along with 35,000 others planning for the day he can return home and restart his business capturing life’s simple pleasures.