Grieving Mother Holds On to a Prisoner’s Memorial to her Son

Martha has lived in Nariño Department in the southwest of Colombia, close to the border of Ecuador, for many years, forced from her home in neighbouring Putumayo by armed men who seized control of the municipality and murdered eight members of her family.

Seated in the living room of her modest but comfortable apartment, she retells her journey, about the death of her first-born and her quest for justice.

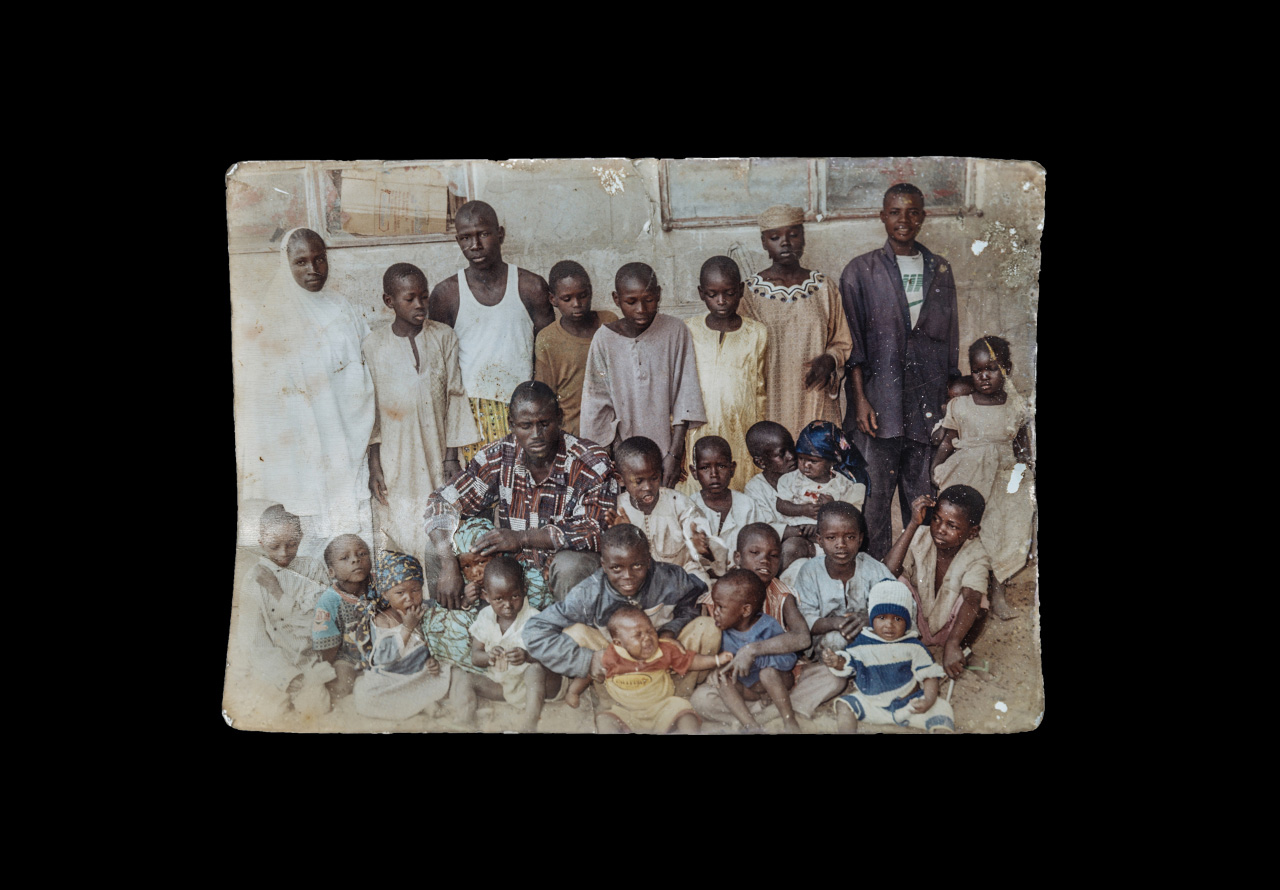

She left the school she founded for the last time on 21 August, 2001. Martha, then a 45-year-old mother of seven, and her husband sensed they were being followed by unknown people and were in danger. They managed to evade whoever it was, but it was clear her activities as a community leader had caught the attention of people who would do her harm. She and her family were about to be swept up in the unpredictability and violence of the times.

"When I arrived home, my son, pale and frightened, told me, ‘Mom, the paramilitaries came. They said, “Tell your parents we will come back later”.’ Armed groups had already killed many people there. They dismembered them, they threw them into the river... so we knew what awaited us."

They immediately fled town.

Life on the run in unfamiliar places with so many mouths to feed proved so difficult for the couple that by 2003, Martha had resigned herself to returning to Putumayo on her own. Paramilitaries were waiting the day she arrived back: for four days she was disappeared.

Again, her eldest son, now aged 25, intervened, likely saving her life. He gathered information and worked with a police friend to identify the location where she was being held. Martha was rescued but the incident was not forgotten. A short time later, the people behind her abduction took their revenge, ordering a local farmer who had joined the paramilitaries to murder the young man.

“I wanted to die because I’d lost my eldest son, the one who always held my hand, the one who was like a father to my other children,” says Martha, 17 years later. “I swore before the body of my son that I would not rest one day, one minute, until I found who killed him.”

She began hunting his killer armed only with a mother’s grief and the camera and tape recorder her son had planned to use once his medical studies began at a university in Ecuador. Four months later, she’d identified the person responsible and handed him over to the police.

“Justice would be served. Not in full, but at least some justice, and this minimized my pain,” she recalls.

Later, as part of her efforts to heal, Martha visited the Mocoa prison where the gunman was serving his sentence. The prisoner in the adjoining cell was knitting quietly and listening to the exchange between the mother and her son’s killer. He heard his excuse – “I was just following orders” – and her grief at the lack of remorse.

“He heard my sorrow. He told me that he was going to make a hammock stitched with my son’s name, Edwin, in his honour,” she says.

“I keep it in a small bag together with the shirt my son wore when he was killed, the camera and tape recorder. Wherever I go, I always carry them with me.”

Edwin was not the only victim in Martha’s family; seven others were murdered or forcibly disappeared over the years.

“Looking back, I see that as victims of forced displacement, we did not have the support that (other displaced persons) have today,” says Martha. “We never received psychological treatment that would have helped us minimize our pain and mourn. We had to heal on our own. Today, many organizations have recognized our suffering, and are helping victims overcome some of their pain.”

Over time and with the assistance of USAID-funded IOM programmes for victims of violence, Martha has emerged as an articulate spokesperson for survivors. But her son, alive in the articles she is holding on to, is never far from her thoughts.

“I see my son in these objects; they represent his memory. Time passes but his memory lives with me every day. Every day feels like the first day I lost him,” she says. “By telling my story and the story of several other women who suffered these same tragedies, I am becoming more resilient to the pain I have suffered.”