Abaco – When he wasn’t studying, 15-year-old Brandon Severe spent his days on the Bahamian island of Abaco racing up and down farm roads between pine trees and citrus fields, determined to improve his sprint time.

His father Maurice, a heavy equipment operator, could not have been prouder of his son’s first place finish at his high school athletic competition in the capital Nassau, last year.

Maurice last saw his son on a tumultuous day ten months ago when Hurricane Dorian tore through their home in Abaco, before putting him on a boat which took him to safety on another island.

“I knew there’d be no school here and I don’t want my kids to be here to watch all of this. I just want what was best for them, to help them as much as I can. That’s what dads are there for.”

Packing winds of 280 kilometres per hour, Dorian slammed into the Caribbean nation in September of 2019, coinciding with an exceptionally high tide that caused severe flooding.

It’s the most powerful hurricane to strike the country since records began – affecting more than 70,000 people and destroying an estimated 3,000 homes. The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) reports that the category five storm triggered about 9,800 new displacements across the archipelago.

According to IDMC, disasters provoked nearly 25 million new displacements worldwide in 2019 – three times the rate of displacement caused by conflict and violence. Almost half of disaster-induced displacement was caused by cyclones and flooding.

Many residents of the most affected island, Abaco, fled to nearby islands by boat or plane. Thousands were hosted in government-run shelters in repurposed school gymnasiums or other places in Nassau - the majority of these residents came from the Haitian community.

On-going efforts to build back affected areas are now more complicated by the emerging COVID-19 pandemic. Due to restrictions on the movement of goods and people between islands, reconstruction on Abaco has slowed as building materials become harder to find. Much of the island is still without electricity.

Members of the Haitian community living in informal, less developed and insecure settlements on Abaco island were among the hardest hit.

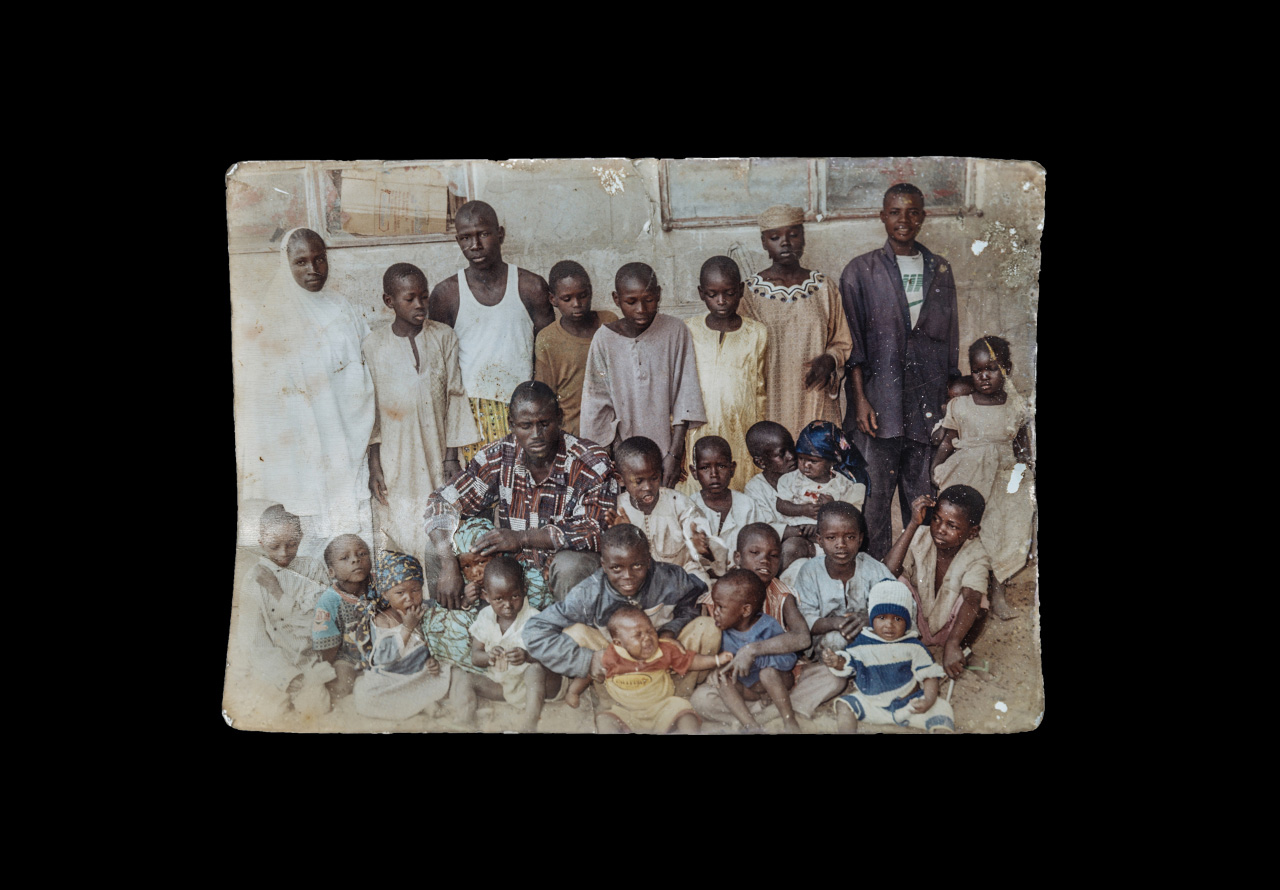

Maurice, a Bahamian citizen, was born to Haitian parents – two of the thousands who came to the Bahamas to work during the tourism boom of the 1980s and 90s.

Like many migrant workers around the world, families of Haitian descent in the Bahamas tend to live below the poverty line and in informal settlements, face continual discrimination and lack access to basic services such as running water, electricity and education.

It’s no surprise then that the effects of Hurricane Dorian were particularly devastating in the settlements that most Haitian communities in the Bahamas called home. Chief among them is one known locally as The Mudd, and another known as The Farm.

“It was blowing hard and then all of the windows started shattering,” Maurice recalls of the day Dorian destroyed his home in The Farm. He ushered his wife, three children and a friend to the living room.

“I told them, ‘When I say duck, all of us have to get down!’ Immediately after that, a sheet of plywood flew over our heads.”

Eventually the roof was ripped off. Maurice took his family through the nearby pine forest, seeking safety further inland. They clung to trees and hid under cars for the next five hours.

“At one point my wife yelled out, ‘there’s a tin coming, there’s a tin coming!’ But before my kids could turn around, the tin caught my son’s leg right behind the knee and cut him open.”

Maurice spent the next few hours at Brandon’s side, using dried tomato paste he found among the debris from the storm to stop the bleeding.

Hours later, he was finally able to get his son aboard a boat to safety.

“The boat had come all the way from another island. It found us, picked up my son and took my son to the hospital.”

Eventually, all of Maurice’s three children – Brandon, Christopher and Maurisha – made it to Canada and the United States where they live with relatives who opened their homes.

Maurice and his wife were among those who remained on Abaco. They have been sleeping in a tent next to a pile of debris that was once their four-room home.

One day while sifting through the rubble, Maurice found his son’s First Place running trophy sticking out amid the ruined clothing and battered couches.

“Finding his trophy really brought back some memories of me and my son. He worked really hard for that trophy. He was always training, running up and here down the road in the Farm. He always made me proud.”

Maurice has joined reconstruction efforts, working with fellow community members as they rebuild their neighbourhoods, homes and lives.

He now spends his days working for famers who employ him as a day labourer, bulldozing destroyed buildings and clearing away the debris.

I got a plan drawing for my house, and I stick to it.

So, I have my property in Marsh Harbour that’s where my mind poised to build my house, my new house, for my kids.

You got to have a place where to lay your head.

And you’ll get all your kids and everybody will come back, and my sister will come, ones are from Canada and all of that from the States, and they’ll be happy.

In his spare time, Maurice is building his dream home.

“My wife, she said to me, ‘Maurice if we go, we won’t have a home later. If you want to come back home, you need to have a place to lay your head.’

I said ‘Well, that makes plenty of sense that’s why I ain’t leaving yet’.”

He pulled together his savings and bought new land in a few kilometres away in an area called Marsh Harbour. It’s a peaceful place, he says – somewhere his mind can relax. He envisions his children playing in the front yard there one day.

“It’s not only me building this house but also a couple of friends. We’re all putting this together and as we work, we crack jokes and make it happen together, through teamwork.”

His plans for the house include three bedrooms, two bathrooms, a living room, kitchen and laundry room.

“Before I start to build though, I need to make sure my wife and my children are happy about the plans for our new home. I’m building this house just for them.”

“When everyone comes back, they’ll be happy, and we’ll all be home together.”

Learn more about IOM’s work responding to the effects of climate change and disasters and support our work through the #FindAWay Campaign.